In health advertising, the bar for content is high: advertisers are expected to apply greater scrutiny to their placement , users assume a baseline level of credibility, and regulators pay closer attention to how health-related information is framed and distributed.

That’s precisely what makes health such a fertile environment for AI slop.

We recently investigated the growing volume of AI-driven pages appearing in the health and wellness environments. These sites rarely look unsafe on their surface and tend to comply with brand safety rules. However, observed at more closely, they signal a quieter, more damaging problem: a growing pool of content that appears credible enough to monetize, but thin enough to erode trust and long-term value.

Why health is uniquely exposed

Health content sits at the intersection of high advertiser demand and heightened sensitivity. Categories like fitness, nutrition, mental health, and general medical guidance attract consistent budgets, particularly from those brands that want to associate with care, self-improvement, and wellbeing.

Because of the nature of this so-called “Your Money or Your Life” (YMYL) content, Google’s Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines underline that it must demonstrate Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trust (E-E-A-T). In the open web advertising ecosystem, however, most buying systems are still optimized around proxies. And when AI-generated health content is designed to meet those proxies, it can absorb spend without ever delivering the credibility advertisers believe they are buying.

How AI-generated health content stays compliant while draining value

Most verification systems are built to catch what are deemed “clear” violations. In health, this tends to mean blocking dangerous claims, prohibited topics, or explicit misinformation.

AI-generated health content rarely triggers those filters.

Instead, it tends to operate in a grey area between compliance and credibility. In addition to avoiding strong claims, these pages follow suitability rules and therefore check most boxes for automated review. What they lack is depth, accountability, and genuine medical authority. This gap allows AI content to scale quickly while remaining difficult to flag, even as it delivers little in terms of value to users or advertisers.

When we examined AI-generated pages at the site level, three consistent patterns emerged.

- Authority cues without accountability: Across health content in particular, we observed repeated author names, vague credentials, and author profiles reused across multiple unrelated domains. Pages adopt the visual language of expertise without the structures that normally support it.

- Compliance-first language: AI-generated health content is careful by design. It avoids absolute claims, leans on generalities, and relies heavily on disclaimers. That restraint helps it pass suitability checks, even when the content adds little beyond what already exists elsewhere.

- Engagement shaped by structure, not intent: In health categories, engagement is often manufactured through layout rather than earned through trust. This can include multi-step explainers, pagination, or comparison-style flows that encourage continued clicking without increasing understanding.

Seeing health supply for what it is – at the page level

To understand why AI slop is especially dangerous in health advertising, it helps to consider an actual page: “If You See These Painful Red Bumps, You May Have Dyshidrotic Eczema” from Boreddaddy.com.

At a glance, its language is cautious, and it doesn’t push illegal treatments or make any promises that it can’t back up. From a brand safety standpoint, it checks all the boxes.

boreddaddy.com

Looked at more closely, the cracks become obvious. The article is attributed to an author with no medical degree, clinical background, or relevant dermatological expertise. That same author name appears across hundreds of unrelated articles, spanning health symptoms, lifestyle content, and viral culture topics. There’s also no indication the piece was reviewed by a medical professional.

Engagement signals reinforce the issue. Despite claiming significant traffic, the page shows no comments or visible reader interaction. What appears to be scale is really just volume: impressions without participation, reach without response.

The content itself is intentionally non-specific. Symptoms are described in broad terms, uncertainty is padded with disclaimers, and readers are given no clear guidance on how to distinguish between benign conditions and those requiring medical attention. There are no citations, no clinical references, and no sourcing beyond the article itself. The tone sounds careful, but the information doesn’t meaningfully inform.

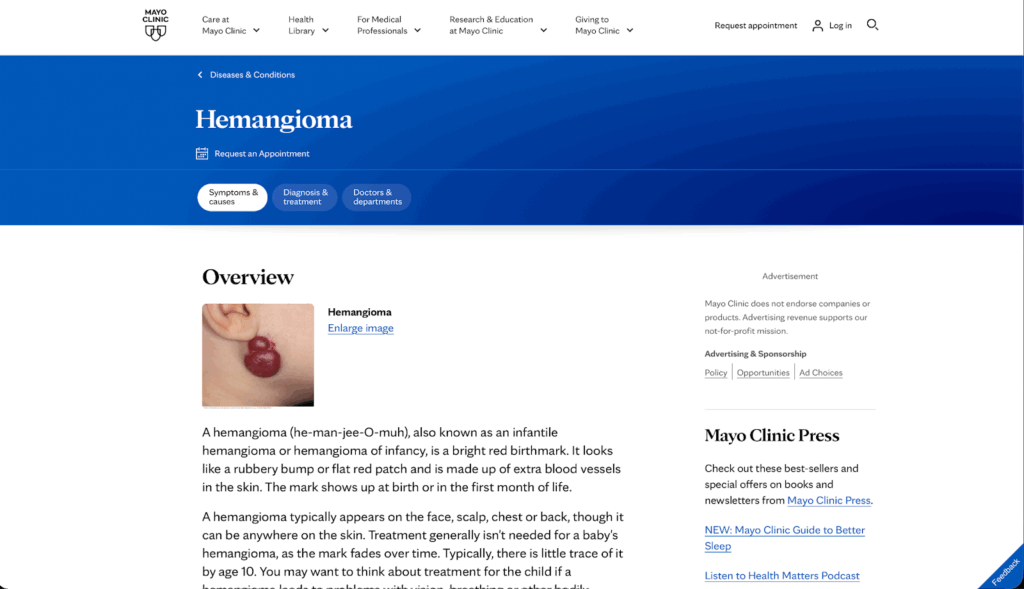

Placed alongside a comparable explainer from a reputable medical publisher such as the Mayo Clinic, the difference is stark. Authorship and medical review are clearly disclosed. Contributors are practicing physicians with defined credentials. Symptoms, causes, and treatment paths are separated cleanly, and readers are told explicitly when to seek professional care. Accountability is visible, and institutional reputation is on the line.

mayoclinic.org

Both articles stay within safety guidelines and both avoid extreme claims, but only one makes it clear who is responsible for the information and why readers should trust it.

When compliant health content erodes value

Pages like Boreddaddy don’t need to be factually wrong to create risk. By operating within compliance, they borrow the surface signals of medical authority and benefit from the trust those signals imply . Buying systems reward those signals (pageviews, time on page, layout-driven engagement) without distinguishing between real clinical oversight and content that merely resembles it.

At scale, this is how health advertising quietly loses value: brands think they’re aligning with care and credibility, all while spend flows to content with artificial authorship and hollow engagement.

To see how these dynamics play out across the open web, download AI Slop and the Collapse of Quality Signals in Programmatic, where we show how observed data helps advertisers identify trustworthy environments instead of wasting budgets on synthetic credibility.